The long and awful beginning

Hilary Horlock’s cancer diagnosis triggered a double shock. On top of the trauma of learning she had a form of breast cancer called invasive lobular carcinoma, Hilary, an employee of the Provincial Health Services Authority (PHSA) in British Columbia, found that the way the health system communicated with cancer patients left much room for improvement.

To start, between Hilary’s diagnosis and her first meeting with an oncologist, more than two months went by. “I got my diagnosis on June 6, 2015, and I didn’t get to talk to an oncologist for 69 days after that. It was an enormous amount of anxiety-filled time to wait.”In that time, she also had to make life-altering decisions. “Within a week of diagnosis, I was referred to surgery, and there I had to decide between total mastectomy, lumpectomy, or a version of a lumpectomy. All of the decisions that I made in June about my upcoming surgery on July 2 would have future treatment implications when I finally got to meet the oncologist in August,” she explains.

All of this she and other patients face at a time when “you’re not always absorbing and processing everything well because you’re reeling from one shock to the next.”

“This wasn’t a question of care,” says Hilary. “BC Cancer delivers world-class care and compassion. In those 69 days between my diagnosis and meeting with a specialist, critical conversations were happening between the appropriate experts, and my care path was created.” The challenge, she says, is that patients don’t know those conversations are happening.

More than that, the communication she did have wasn’t always delivered around the touchpoints she felt were important to her as a patient. For example, information packages on her chemotherapy protocol were multiple pages long, organized by drug name. “Giving me a list of side effects that was organized around the complex oncology drug names not only wasn’t helpful, it reinforced the scariness of what was ahead.”

So, as she stared down the reality of being a patient, Hilary took up the role of advocate, seeking to improve the experience for all women in BC facing a breast-cancer diagnosis and journey.

Changing breast-cancer conversations

In March, 2016, we joined Hilary’s team. Our objective? Understand the communication experience from the patient’s perspective so that, eventually, breast-cancer care teams would have more patient-friendly communication tools designed around the topics and timing that patients deemed important.

“We interviewed caregivers and oncology specialists. We mined information from patient blogs. We read medical journals, and most importantly, we led patient interviews,” says senior Habanero consultant Cat Sanders.

Cat and team member Christina Ferancik sat down for individual interviews with six women, all in various stages of recovery. The research was affecting and deeply personal, Cat recalls. But more than anything else, it was awe-inspiring: “Although some women were only a year past their treatment, all of them wanted to help. They wanted to improve the journey for other women. There was a sense of empowerment in that.”

Understanding the communication experience meant capturing each woman’s thoughts and emotions at various stages in their cancer journeys, such as detection, preparation for surgery, and the first round of chemo. It also highlighted trends, and a significant one was noted.

“When both mental and physical health are compromised, a patient has her most vulnerable moments. It’s during these moments that intervention has the most impact,” says Cat. Hilary refers to this as one of the project’s “a-ha” moments, and an awareness of a patient’s vulnerability would become one of the core guiding principles of the project’s action plan.

Hilary emphasizes another guiding principle that came through experience and research: “As patients, what we really need is understanding, not information. That’s the biggest thing for me: turn information into understanding. So, for example, how can we help patients at the very beginning of their journey when they receive a copy of their pathology report? It’s a really vulnerable moment, but there are no patient-friendly guides to help women understand the content of that complex document that’s telling them they have cancer. And how can we better inform women about the side effects of chemo before it starts, also a really vulnerable moment?”

Hilary and Habanero are now tackling these two opportunities. They were two of many identified during the research phase and prioritized in an action plan, which is a vital companion to the patient journey map. At the same time, BC Cancer’s new strategic plan is addressing systemic challenges, such as the centralization of cancer care, that were evident in several patient stories.

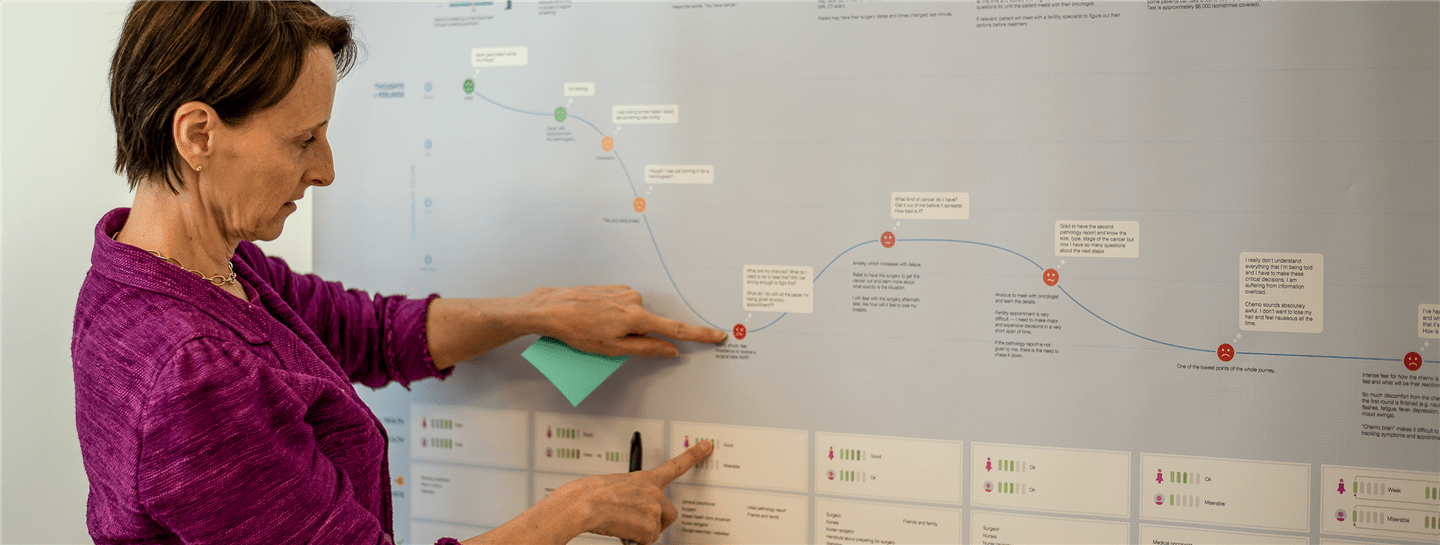

All the while, Hilary continues to tell the important story that we documented as a patient journey map. Printed on nearly indestructible vinyl and shared broadly as a digital PDF, the map is helping BC Cancer staff and decision-makers see the journey through patients’ eyes and experiences.

“The map is an invaluable tool for clinical teams to see where the patient is, what her fears are, and how vulnerable she might be at each step in the process,” says Hilary.

A future full of empathy

“The feedback we’ve had from medical professionals is that insight communicated in the journey map really helps them step into a patient’s shoes,” says Cat. “That’s what it was all about—a means to engender empathy.”While the research we carried out together has already changed the conversation about breast-cancer care, Hilary hopes that clinical teams will be able to use the journey map as a template for other cancer journeys, taking our lessons learned and customizing their own information design for their specific groups.

“We have a phenomenal health care system. It’s truly world-class. I and many others are alive because of it and the team at BC Cancer. This project isn’t about care quality. It’s about seeing care through a patient lens because that’s truly the first step in improving patient-centred care.”